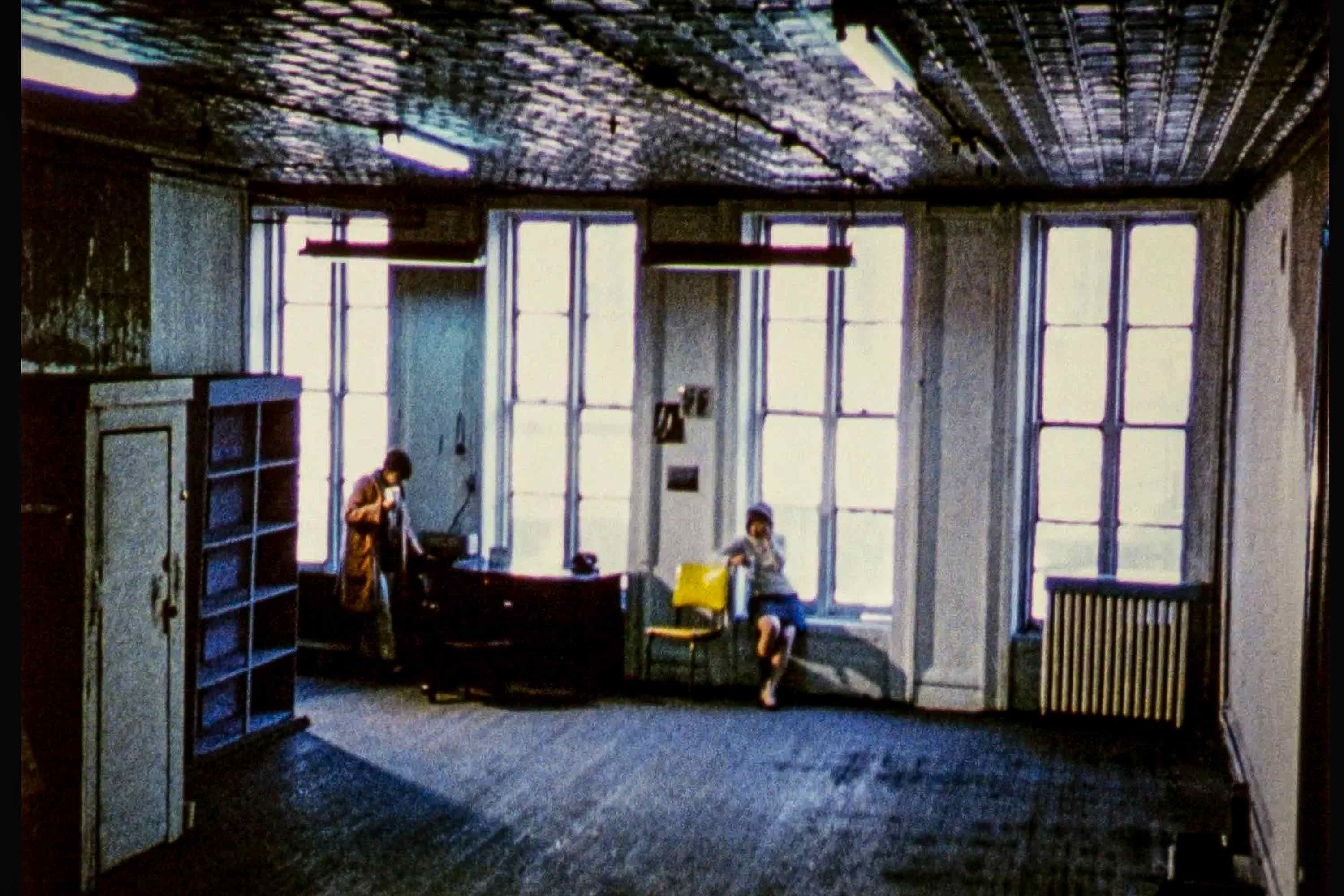

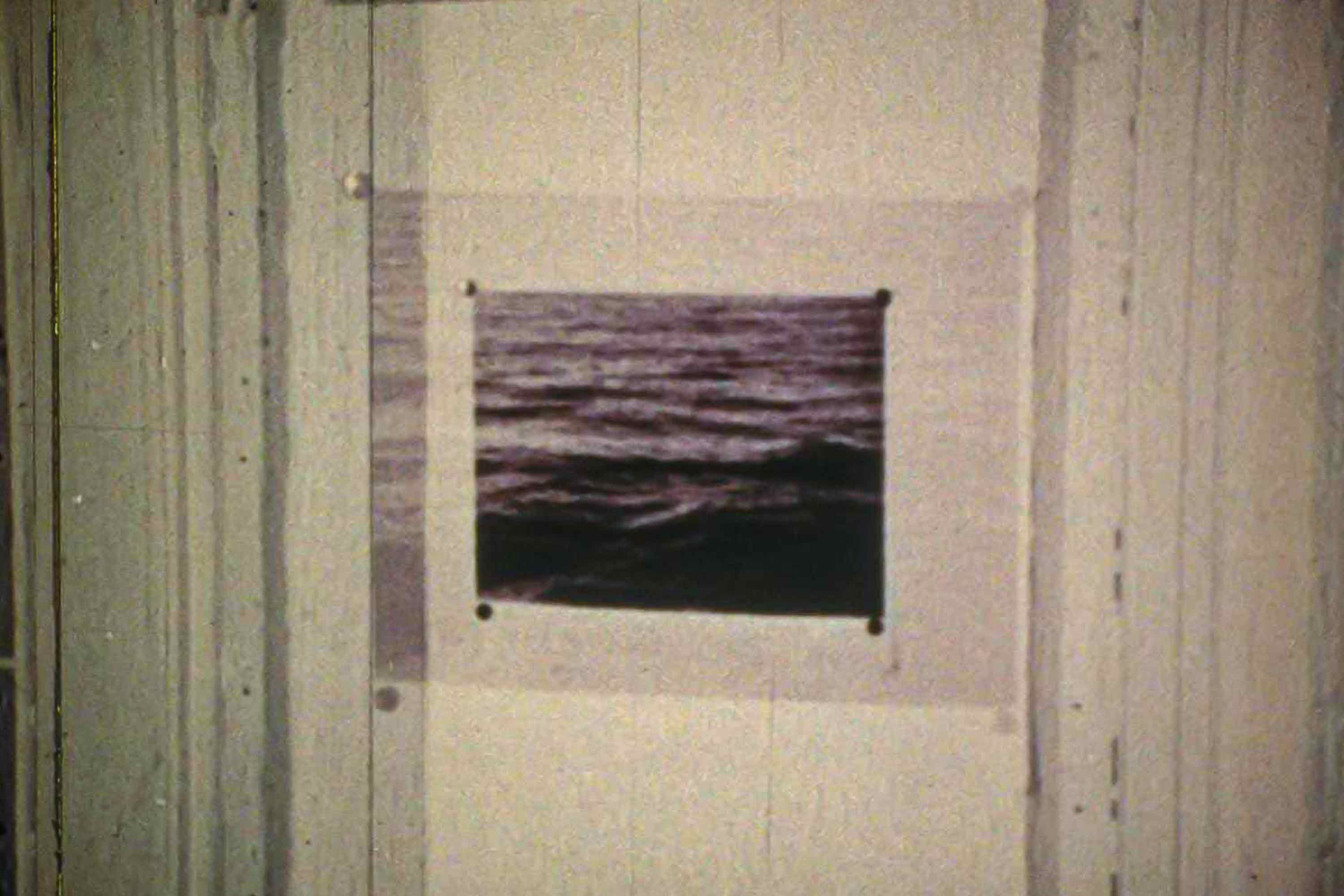

Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) consists of a 45 minutes camera zoom travelling across the entire artist’s studio in New York. The camera is placed at a considerable high point and, although always fixed, its zooming gaze proceeds to slowly move in the direction of the opposite wall. Through the windows, we can notice outside activity of human movement and traffic passing by and, at a certain moment, an unexpected sound is triggered — an electronic sine wave which progressively raises its pitch — functioning as a sort of parallel to the piercing zoom. The camera’s gaze doesn’t seem to stop and its framing goes way beyond the windows, and we are now pushed against the wall, finally finding its resolution in a black and white photograph of sea waves, gently blurring itself finally reaching a pure final white canvas: the frame of the screen, as an outline for the moving-image, dissolves and melts down with the still-image of the sea waves into a new woven image of nothingness.

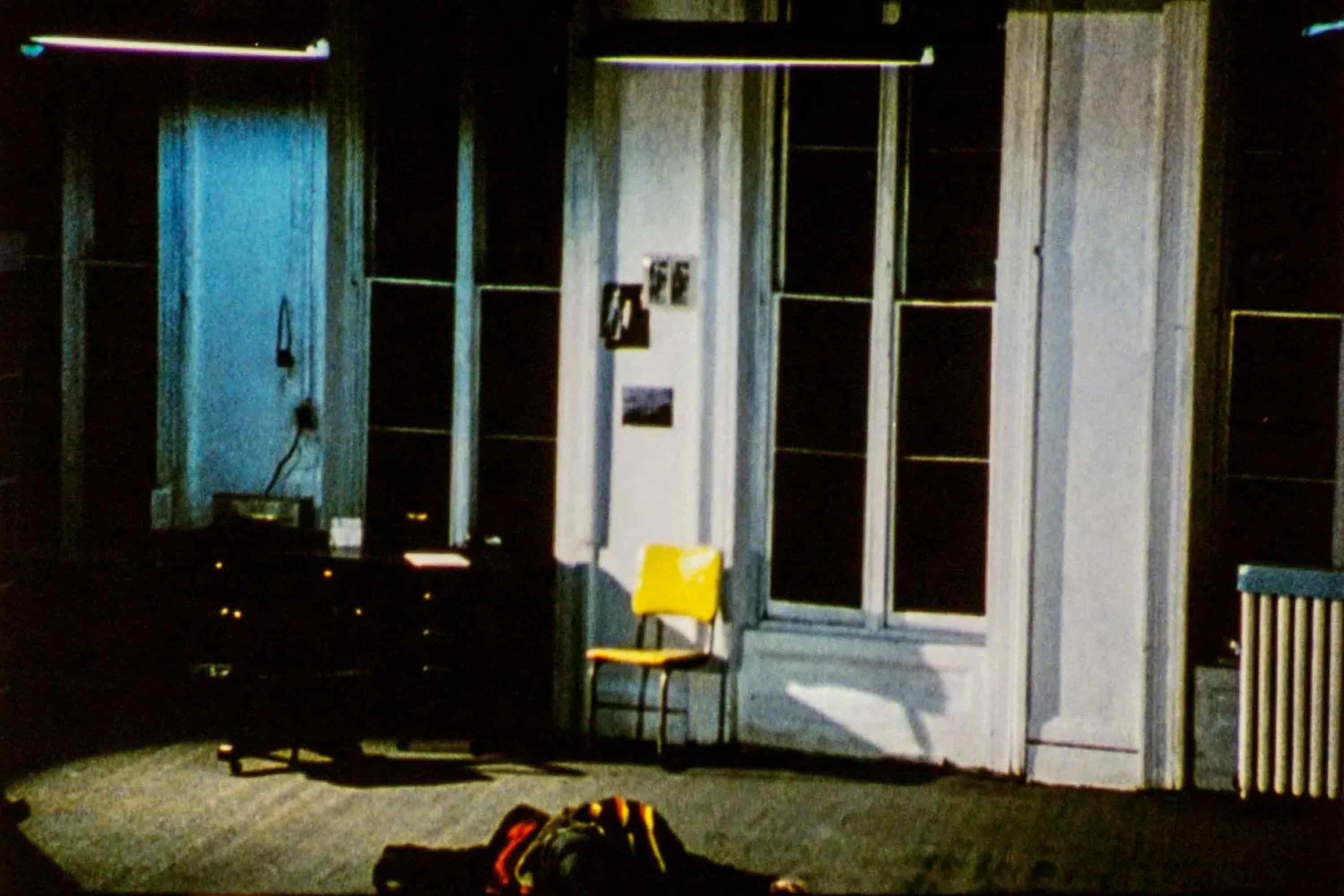

Several human actions take place throughout the film, distanced, unannounced, seemingly discrete, but equally abrupt at times, hinting at possible minor connections through only a few lines of dialogue and collected silent gestures. In the beginning, three individuals occupy the studio: two men carry a piece of furniture while a woman tells them where to leave it. Following up, two other women enter the studio, one of them closes the window while the other turns on the radio. Both exchange absolutely no words while they listen to The Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever. Later on, we hear a sudden crash or shattering sound of what seems to be glass breaking and, immediately, we see a man entering the studio by suddenly falling onto the ground, as if passed out or even dead, whose body we can only partially notice due to the ever-lasting camera zoom. With the last human presence, a woman comes in, walks to a telephone, and warns someone on the other side that there seems to be a dead man on the floor. We are given no more context neither do we find any resolution to these interactions, and so the lyrics of The Beatle’s song start to echo in us a sense of alertness: Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.

In addition to these human happenings, a series of film happenings also take place whilst the zoom keeps on unfolding, not so perfectly seamless, but with certain wobbles and stutters. At a certain point, there are changes and variations to the exposure of the image, flashes of light ranging in various intensities, the film negative is deliberately presented, certain shifts in colour transfigure the skin of the film, splashes of flicker effects, superimpositions and other improvisations with different materials. Michael Snow himself stated: «I played/improvised with plastics and filters while shooting, bearing in mind many considerations, such as their relationship to the human images» (Snow, 1994, p. 52). Just like the image, the sound is also primarily presented through noises which we take as real — cars, steps, conversations between people — until, at a given moment, we are introduced to that tone which slowly and gradually becomes higher and higher as the zoom progresses. Knowing Michael Snow to be a free jazz player, Randolph Jordan (2010, p. 170) would establish a curious analogy between these material improvisations done by the artist throughout the film, in the sense that both Wavelength and a jazz theme present a sort of foundational skeleton as an envelope, a temporal integument for the formal pieces which bring it into shape. In Michael Snow’s case, the zoom would correspond to that first foundation, to those first chords which establish the outline for the music theme, giving it a tangible coherence to navigate in, whilst all other physical operations, activities and interactions — both human and filmic — would nurture its destiny just like the improvisation of the guitarist unveils the true colours of the chords, just like the improvisation of the drummer unravels unexpected rhythms within an already presupposed established cadence, sustaining it, fulfilling it, bringing it into life. Its structure is always there, invisible as an horizon which outlines the entire of our surroundings, meanwhile all the other elements bring that structure to the fore in the most variable of ways.

Several human actions take place throughout the film, distanced, unannounced, seemingly discrete, but equally abrupt at times, hinting at possible minor connections through only a few lines of dialogue and collected silent gestures. In the beginning, three individuals occupy the studio: two men carry a piece of furniture while a woman tells them where to leave it. Following up, two other women enter the studio, one of them closes the window while the other turns on the radio. Both exchange absolutely no words while they listen to The Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever. Later on, we hear a sudden crash or shattering sound of what seems to be glass breaking and, immediately, we see a man entering the studio by suddenly falling onto the ground, as if passed out or even dead, whose body we can only partially notice due to the ever-lasting camera zoom. With the last human presence, a woman comes in, walks to a telephone, and warns someone on the other side that there seems to be a dead man on the floor. We are given no more context neither do we find any resolution to these interactions, and so the lyrics of The Beatle’s song start to echo in us a sense of alertness: Living is easy with eyes closed, misunderstanding all you see.

In addition to these human happenings, a series of film happenings also take place whilst the zoom keeps on unfolding, not so perfectly seamless, but with certain wobbles and stutters. At a certain point, there are changes and variations to the exposure of the image, flashes of light ranging in various intensities, the film negative is deliberately presented, certain shifts in colour transfigure the skin of the film, splashes of flicker effects, superimpositions and other improvisations with different materials. Michael Snow himself stated: «I played/improvised with plastics and filters while shooting, bearing in mind many considerations, such as their relationship to the human images» (Snow, 1994, p. 52). Just like the image, the sound is also primarily presented through noises which we take as real — cars, steps, conversations between people — until, at a given moment, we are introduced to that tone which slowly and gradually becomes higher and higher as the zoom progresses. Knowing Michael Snow to be a free jazz player, Randolph Jordan (2010, p. 170) would establish a curious analogy between these material improvisations done by the artist throughout the film, in the sense that both Wavelength and a jazz theme present a sort of foundational skeleton as an envelope, a temporal integument for the formal pieces which bring it into shape. In Michael Snow’s case, the zoom would correspond to that first foundation, to those first chords which establish the outline for the music theme, giving it a tangible coherence to navigate in, whilst all other physical operations, activities and interactions — both human and filmic — would nurture its destiny just like the improvisation of the guitarist unveils the true colours of the chords, just like the improvisation of the drummer unravels unexpected rhythms within an already presupposed established cadence, sustaining it, fulfilling it, bringing it into life. Its structure is always there, invisible as an horizon which outlines the entire of our surroundings, meanwhile all the other elements bring that structure to the fore in the most variable of ways.

Despite Snow’s deliberate improvisation with these different formal and material aspects of the filmic apparatus, both these aural and imagetic transfigurations do not come into play by mere inconsiderate chance. The light and colour variations, or the transitions into negative, have as much importance to the film as the furniture which is carried by the human bodies, or the man who goes from an active state (living body) to an inanimate one (object). What Snow attempts to create is, like he so pronouncedly asserts throughout his films and writings, a balance between all the realities involved in the making of a film, in order to establish that, throughout the phenomena we experience, he always takes into consideration both the representational level of the image — a space that is immediately familiar to us, possessed of a living and believed significance — and, simultaneously, the formal and material level of the image — the physicality of the celluloid strip as the actual corporeal materiality which supports the living weight of the film. Michael Snow insists on both a perceptual and conceptual entanglement between both as to bring us to the realization that one is always woven into the other, even if we so forget that simple fact. Once seated, the spectator begins by immediately being pulled into the screen, invited within its framing, to inhabit the illusory space it circles and encloses, only until, at a certain moment, to be confronted by its flat surface as if a wall had suddenly mysteriously appeared: «Things happen in the room of Wavelength, and things happen to the film of the room» (Sitney, 1974, p. 416).

Snow has not forgotten the indexical quality of the photographic and cinematic image Bazin (2005) so elegantly reflected on, our irrational belief in its objective power, but, as a deeply conscientious artist, he knows the medium all too well and recognizes all the immense perceptual, material and structural qualities that are born from within the medium. Margarida Medeiros (2010) traveled through the magic and ethereal world of the living dead in photography by showing us its capacity to freeze temporality on our hands, its mummyfying aspect, its suspended state between death, sleep and imobility, and the spectacle of ghostly images created by spiritual photographs that were believed to communicate with the other world. The work of André Bazin, Margarida Medeiros, Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag has allowed us to understand that cinema is not a perceiver of worlds, but a perceived world, a world within initself, and, as such, a world within worlds, for it is embedded with this complex capacity to represent (some kind of recognizable gesture), re-present (reality as we believe to perceive it), and present (itself as itself, devoid of any immediate signification).

With this, we might consider that there is always, in Wavelength, a certain interwoven relationship or interplay between the tridimensional magical space the screen opens onto and the complete bidimensional depthless terrain which the film, as a mechanical medium, always factually presents. When the studio is inhabited by human actions (and the film starts precisely with them) we have a seamless three-dimensional notion of that space. However, when the studio becomes empty and silent for some time and we are presented with — even if very few — changes of light and colour on the image, our gaze starts to focus on the plain surface of the canvas. We, henceforth, start to acknowledge the film strip, precisely, as that shrouding horizon, as that outline for the structure of the whole body of film, embarked with all of the unique properties which bring it into being without a need for any symbolical, metaphorical or even poetic correspondent: pure empty light acting on its own, colour revealing itself in negative or positive formats, tangible film grain and texture nevermore seen as flaw or inaccuracy, mechanical camera operations acting on their own, durational endurance and awareness and a moving frame which slowly excludes from our sight everything beyond its limits.

Some of the human events that take place are, inevitably and very clearly, embodied clues of this realization: the heavy furniture which is moved from one place to be fixed in another, the living subject which drops dead on the floor. The black and white photography of the waves functions as the climax of this idea: what we have is a transfiguration of the movement of the zoom which pierces the whole depth of the studio until it reaches a frozen image of the waves as if we had just ran into a transparent glass with our heads, which was always there, but we couldn’t actually see. It shakes us up, it awakens our creative intuition from some sort of dormant condition which commercial cinema so inherently operates under like a haunting veil. It brings us back to ourselves so that we can realize that we have a synergetic participation to the whole being of film. In turn, the framing outline of the waves immediately snaps together juxtaposed with the square of the screen in order to finally conclude that interlaced dichotomy: that film is nothing but the rapid succession of stillness generating the illusion of animated motion not through the apparatus itself, solely, but through its entanglement with my perceptual act: the film is born within my eyes and ears.

Snow has not forgotten the indexical quality of the photographic and cinematic image Bazin (2005) so elegantly reflected on, our irrational belief in its objective power, but, as a deeply conscientious artist, he knows the medium all too well and recognizes all the immense perceptual, material and structural qualities that are born from within the medium. Margarida Medeiros (2010) traveled through the magic and ethereal world of the living dead in photography by showing us its capacity to freeze temporality on our hands, its mummyfying aspect, its suspended state between death, sleep and imobility, and the spectacle of ghostly images created by spiritual photographs that were believed to communicate with the other world. The work of André Bazin, Margarida Medeiros, Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag has allowed us to understand that cinema is not a perceiver of worlds, but a perceived world, a world within initself, and, as such, a world within worlds, for it is embedded with this complex capacity to represent (some kind of recognizable gesture), re-present (reality as we believe to perceive it), and present (itself as itself, devoid of any immediate signification).

With this, we might consider that there is always, in Wavelength, a certain interwoven relationship or interplay between the tridimensional magical space the screen opens onto and the complete bidimensional depthless terrain which the film, as a mechanical medium, always factually presents. When the studio is inhabited by human actions (and the film starts precisely with them) we have a seamless three-dimensional notion of that space. However, when the studio becomes empty and silent for some time and we are presented with — even if very few — changes of light and colour on the image, our gaze starts to focus on the plain surface of the canvas. We, henceforth, start to acknowledge the film strip, precisely, as that shrouding horizon, as that outline for the structure of the whole body of film, embarked with all of the unique properties which bring it into being without a need for any symbolical, metaphorical or even poetic correspondent: pure empty light acting on its own, colour revealing itself in negative or positive formats, tangible film grain and texture nevermore seen as flaw or inaccuracy, mechanical camera operations acting on their own, durational endurance and awareness and a moving frame which slowly excludes from our sight everything beyond its limits.

Some of the human events that take place are, inevitably and very clearly, embodied clues of this realization: the heavy furniture which is moved from one place to be fixed in another, the living subject which drops dead on the floor. The black and white photography of the waves functions as the climax of this idea: what we have is a transfiguration of the movement of the zoom which pierces the whole depth of the studio until it reaches a frozen image of the waves as if we had just ran into a transparent glass with our heads, which was always there, but we couldn’t actually see. It shakes us up, it awakens our creative intuition from some sort of dormant condition which commercial cinema so inherently operates under like a haunting veil. It brings us back to ourselves so that we can realize that we have a synergetic participation to the whole being of film. In turn, the framing outline of the waves immediately snaps together juxtaposed with the square of the screen in order to finally conclude that interlaced dichotomy: that film is nothing but the rapid succession of stillness generating the illusion of animated motion not through the apparatus itself, solely, but through its entanglement with my perceptual act: the film is born within my eyes and ears.

It now makes sense, however, that none of the human actions along the film have any resolution whatsoever. They are the proper manifestation to this conclusion. Under no condition or at any given moment do we see the same character come back nor do we know their following destinations. The film accepts narrative but refuses any dramatic possibility for that is not its main interest. The only reference we are given from the characters who inhabit the studio about the people who have been there before them is when the «telephone woman» acknowledges the «deadman» on the floor, that moving stillness. Not only that, but the actual camera never stops to change its framed composition or angle to focus on any of them, not even when death so evidently comes to visit: the zoom simply continues its predestined goal as if it assumed the role of a main character committed to fulfil eternity’s doing. And so, as we can finally attest to, we can now understand that «Snow is debunking conventional, story based moviemaking, saying, essentially, that narrative events, for his purpose, are not more important than other more strictly formal events that happen in film» (Johnson, 1994, p. 75).

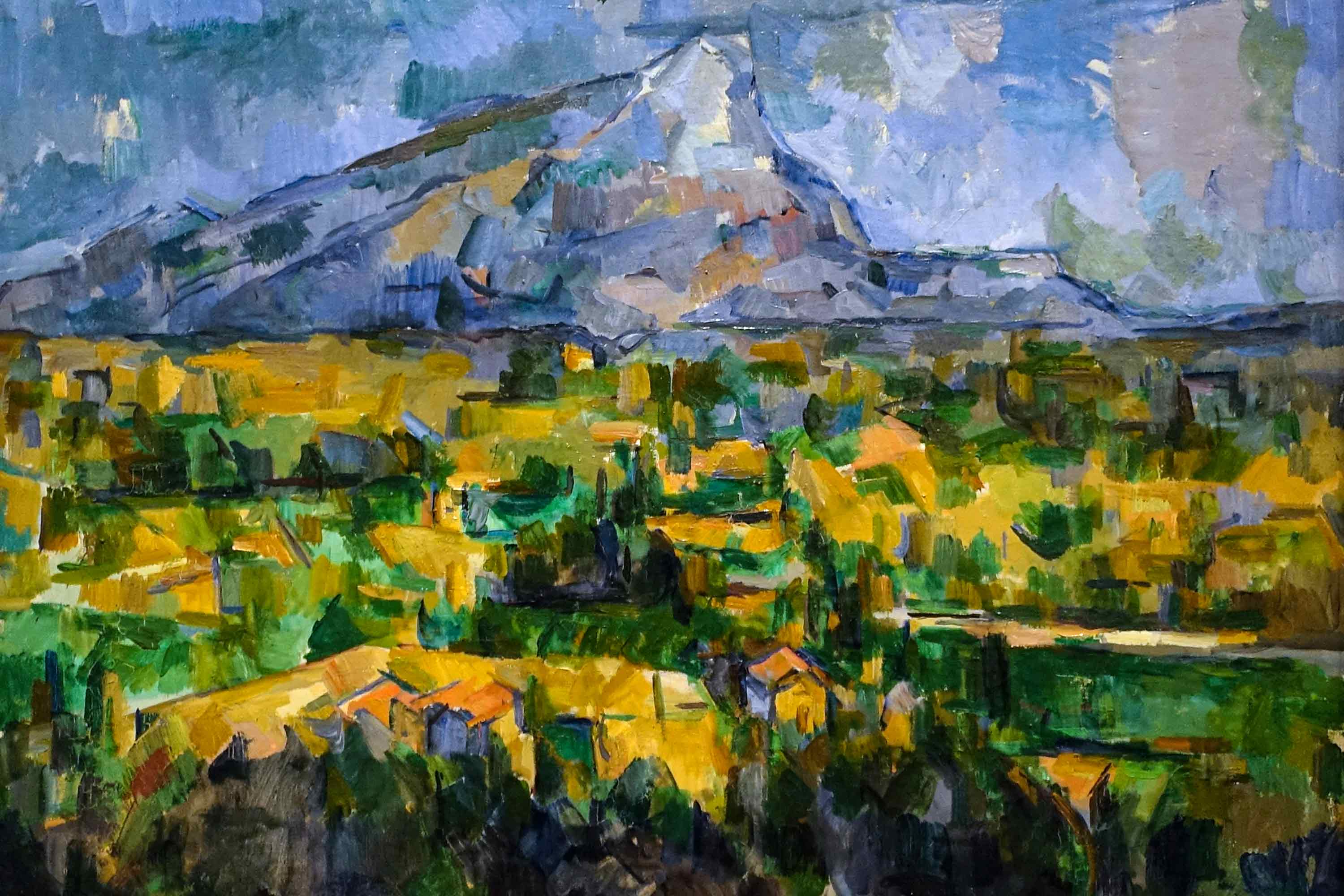

But it is still important to assert that, by going beyond — or parallel to — narrative, Wavelength is never anti-narrative. Narrative is always there, present in the film, to be looked at, but simply never fully realized, never fully intended as the main conductor of the piece. As Duncan White so rightly mentions, any audiovisual expression that has a development in time will always cultivate a hidden narrative potential because it embarks the same form, the same movement as narrative: «Form and movement rather than content suggest that narrative is an activity, something the audience participates in constructing, rather than something that is simply consumed» (White, 2011, p. 111). And so, if one is to try and find any sign of drama or narrative continuity, one can start to wonder if the death was accidental or if it was a murder, since the woman who speaks on the phone doesn’t seem to be in such a shock or rush to help the fallen man: so who is she calling and with what intent? With these very minimal actions, one is given the time to actively search for meaning, to build up a certain expectancy in the small fragments that are given. In a conversation with P. Adams Sitney and Jonas Mekas, Michael Snows takes this discussion of form and content even deeper by comparing Wavelength to the Sainte-Victoire paintings of Cézanne:

But it is still important to assert that, by going beyond — or parallel to — narrative, Wavelength is never anti-narrative. Narrative is always there, present in the film, to be looked at, but simply never fully realized, never fully intended as the main conductor of the piece. As Duncan White so rightly mentions, any audiovisual expression that has a development in time will always cultivate a hidden narrative potential because it embarks the same form, the same movement as narrative: «Form and movement rather than content suggest that narrative is an activity, something the audience participates in constructing, rather than something that is simply consumed» (White, 2011, p. 111). And so, if one is to try and find any sign of drama or narrative continuity, one can start to wonder if the death was accidental or if it was a murder, since the woman who speaks on the phone doesn’t seem to be in such a shock or rush to help the fallen man: so who is she calling and with what intent? With these very minimal actions, one is given the time to actively search for meaning, to build up a certain expectancy in the small fragments that are given. In a conversation with P. Adams Sitney and Jonas Mekas, Michael Snows takes this discussion of form and content even deeper by comparing Wavelength to the Sainte-Victoire paintings of Cézanne:

It is attempting to balance out in a way all the so-called realities that are involved in the issue of making a film. I thought that maybe the issues hadn’t really been stated clearly about film in the same sort of way — now this is presumptuous —, but to say in the way Cézanne, say, made a balance between the colored goo that he used, which is what you see if you look at it in that way, and the forms that you see in their illusory space. (Snow, 1994, p. 41)

From one side, the paint brushes (the paint-as-paint) possess solely within and by themselves a series of visual, material, plastic and abstract qualities: they sustain themselves as themselves and refer only to themselves. However, at the same time, those same paint brushes (now treated as paint-as-a-means-to-represent-something) occupy a certain symbolical significance in the illusory field they inhabit. In other words, the paint has now a figurative role, it represents something: a tree, a mountain, a house, and so on. Our perception can easily travel inbetween both realizations not as separate but interlaced dimensions — one single dimension after all. Snows makes this comparison in order to tell us that, respectively, his work is concerned with the film-as-film and the film-that-represents: it is always within that balance from whence his work comes into life. By bringing this problematization to the surface of modern cinema’s criticism and visual art theoretical research, by holding it in plain sight as the central core of his approach, Snow contributes to emphasize the capacity of film as a means within itself, for itself, without the canonized dependency on commercial tendencies, consequently leading us, as intelligent spectators, to a conscious awareness of our act of seeing and hearing.

Analogous to Cézanne’s “colored goo” is cinema’s projected light falling on the flat surface of the screen. From that fact comes the illusion of solid forms in three-dimensional space. Snow’s goal is to bring the spectator to the fullest possible recognition of both qualities of the cinematic image: its referential nature as representation of the visual worlds and its essential nature as, in Snow’s words, “projected moving light image”. From that recognition on the part of the spectator comes the “dual state”, or balance, of “ecstasy and analysis” Snow desires. Nowhere is it more fully realized than in the “demonstration or lesson in perception” provided by Wavelength. (Wees, 1992, p. 156)

Snow recognizes these inherent particularities of film and constantly takes advantage of them to bring out the spectator’s active role. William C. Wees would continue to address this premise by arguing that all of these properties should be treated not only as crucial perceptual engagements with the full potential of the film medium, but, equally, as fundamentally conceptual: 1) perceptual for they unexpectedly interact with the spectator’s interwoven aural and visual senses, disturbing their nervous system; 2) conceptual because they subvert the conventional illusory space of the cinematographic image by directing the spectactor’s attentive awareness to what, in Snow, is an equivalent to the paint smudges in Cézanne: the material surface of the film strip and the mechanical modes in which it comes to be conceived and presented (Wees, 1992, p. 156). For Snow, the film medium is not a perceptual field closed off separately by these two seemingly autonomous realities, external or independent from one another, but, moreover, and much beyond, the cinematic language is a dialectic coupling of these two enfolding glances which open up and fulfil one another like organs sustaining one intercorporeality, like two lungs breathing life into the same body. It is the reciprocal congruence of these two pronunciations that, ultimately, results in a pure cinematic experience for Snow, an original bestowal of being film.

What we have is, then, a pure elemental cinema: a cinema that does not depend exclusively on any attributes external to itself — on story, on lyricism, on poetry, on emotion — but, rather, a cinema that invests in its own making. And so Snow unravels cinema’s process of becoming inside out, a sort of laying bare of its internal structural dialectic, into an auto-reflexive relationship of the eye and the cinematographic device: from two-dimensionality to three-dimensionality, from stillness to motion, from representational illusion to the raw presentation of all material and physical qualities of the celluloid, from the potential construction of drama and lyrical narrative to a primacy of the perceptual interference of the camera’s mechanical nature and electronic sound into our sensible nervous system. And so Michael Snow continues in the interview with Sitney and Mekas:

What we have is, then, a pure elemental cinema: a cinema that does not depend exclusively on any attributes external to itself — on story, on lyricism, on poetry, on emotion — but, rather, a cinema that invests in its own making. And so Snow unravels cinema’s process of becoming inside out, a sort of laying bare of its internal structural dialectic, into an auto-reflexive relationship of the eye and the cinematographic device: from two-dimensionality to three-dimensionality, from stillness to motion, from representational illusion to the raw presentation of all material and physical qualities of the celluloid, from the potential construction of drama and lyrical narrative to a primacy of the perceptual interference of the camera’s mechanical nature and electronic sound into our sensible nervous system. And so Michael Snow continues in the interview with Sitney and Mekas:

The film opens with the kind of thing in which you have a certain belief or you give up that you see a room, you see people walk in, and you believe in that. The room is shot as realism. It is shot the way you would see a room as much as there is a consensus about how one sees a room. It also has realistic representational sound: the noise from outside. But then there are intimations of other ways of seeing the thing, until the first thing is when the image is totally negative. It is all red and that pure sound, that drone at about fifty cycles per second, starts as opposed to the other representational sounds. That is something in which you do not have the same kind of belief. It is the other side of that, and yet it’s colored light. It is all very obvious. I was concerned with making a balancing of all these things. (Snow, 1994, p. 41)

But this perfect balance is not only apparent in the relationship between the illusory space of the room and the tangible space of the film strip. It is, simultaneously, present in all of its temporal sculpture. In Michael Snow’s Wavelength, time becomes, as Akira Lippit argues, chronic. And if we dive into the etymology of the word we can quickly identify that, from Latin and Greek, the term is both related to the Titan Chronos, to time, to the continuous and constant passage of events, but, simultaneously, to a restlessness, an instability, a disruption, a disease. What is a chronic disease if not the biological attribution of significance to something that undermines healthy time, that erodes it, as a sort of threat to remove us from it or to oblige us to feel its recurrent obsessive endurance? «A vertigo of time that manifests itself perpetually and as a type of disorder» (Lippit, 2012, p. 43). The word encapsulates, then, these two conflictual meanings which are always in constant friction, in constant resistance and tension against one another. We can summarize it, then, here, as a disease of time, a disruption of or in time, a temporal reverie.

In Michael Snow’s Wavelength, time assumes its devouring chronic power because its perpetual appearance is the result of the intersection between different times of the day we see in the film — what appears to us as morning time, evening time or night time, although we were never given the exact hours of the footage — are all interlaced into what is, essentially, in camera editing and montage time. The slow narrowing movement of the zoom produces units of time which are only measured from its projection. It is, in this exact sense, that Michael Snow calls it «a time monument» (Snow, 1994, p. 43), a time sculpture, for neither the production of the film nor the temporal duration it projects on the canvas are absolutely continuous. What we have, then, is a seamless editing inbetween shots that produce an impression of a single uninterrupted fluidity of time through continuous space. This intersection of different times into one single perpetual movement given by the zoom is finally beautifully encapsulated in the image of the ocean: photography as still and cinema as moving finally juxtaposed, fused into one another as an irreversible interruption of one single gesture. We can easily comprehend now the conceptual graciousness of the slow movement of the camera zoom as possessing, in durational time, a series of amalgamated stillnesses that, when so effortlessly put together, consequently attribute to time its unique character, its livingness: they establish the continuity which ensures its passing. The emergence of the photographic image strings physical time to our temporal reverie.

This temporal reverie could be argued to have another dimension: that of endurance. So many have been the fortunate opportunities that I have had to watch this film, that one singular unexpected humorous moment has stayed in my memory since it took place. I invited a few friends who had never experienced the approaches of «underground», «avant-garde» or «experimental» (call it whatever you want) filmmaking to join me for Wavelength at the Cinematheque in Lisbon. After 10 or 15 minutes of film, one of them asked me if the film was just like this, or if there was any issue with the projection, due to how long this «scene» was taking, and due to how aware of time he was while trying to figure out what’s going on in this apartment. I did not reply. Later, his doubts increased when the film strip started to be tempered with by Snow, and he asked me if there was someone messing with the projector upstairs, if there was something wrong with the film. I could immediately recognize in his look, as long-time friends often do, the blissful honesty in his questioning. Immediately, another of my friends replied: «but look, you can still feel coherence within the space despite the film being out of place; it’s like you are playing with crossing your eyes and doubling the images you can actually see, maybe that’s what the filmmaker wanted, for you to take part in constructing the space». While the third (and final) said: «Dude, it’s like a weird slow-motion trip». I did not reply at any moment during the screening. It was too tempting to listen to their observations, and to try and find out new aspects that I might not have considered until then.

My point with paraphrasing this situation is that, after the screening, while thinking of what happened, I later realized that this manipulation of the film strip not only purposely interrupts our sense of real space and continuous time, as we have already established, but that «it also interrupts the flow of our experiencing a film in such a way that we are reminded that we are watching the flowing of footage through a projector» (Sharits, 1978, p. 33). And Snow does it so in these pronounced ways as if possessed by the refreshing originality of that untutored eye Brakhage so often spoke about, untamed, never tempered, purely curious: «My eye, turning torwards the imaginary, will go to any wavelengths for its sights» (Brakhage, 2017, p. 35). The mechanical and material defects suggested by my fellow friends are, after all, nothing more than a blunt awareness of the used film stocks, the visible splice marks and jumpcuts, as well as the superimposition of the overexposed and negative celluloid as clear physical constituents of what film literally is — a chemical and material surface sensible to light. Consequently, their presence in the film alludes to what Annette Michelson termed as a visual obbligato: they create, «within the movement forward, a succession of fixed or still moments» we must be confronted with and acknowledge, for they are precisely the unique events that articulate an allusion to the stillness and separateness of the frames out of which the persistence of our corresponding vision organizes into cinematic illusion» (Michelson, 2019, p. 17-18). By removing the celluloid out of its continuous flow, by superimposing it with itself, Snow reminds us that we are also part of the whole mechanism, that the system of a projected film works because the apparatus plays by way of a certain cadence within our human visual organism: the medium begs to be seen, it speaks to me.

In Michael Snow’s Wavelength, time assumes its devouring chronic power because its perpetual appearance is the result of the intersection between different times of the day we see in the film — what appears to us as morning time, evening time or night time, although we were never given the exact hours of the footage — are all interlaced into what is, essentially, in camera editing and montage time. The slow narrowing movement of the zoom produces units of time which are only measured from its projection. It is, in this exact sense, that Michael Snow calls it «a time monument» (Snow, 1994, p. 43), a time sculpture, for neither the production of the film nor the temporal duration it projects on the canvas are absolutely continuous. What we have, then, is a seamless editing inbetween shots that produce an impression of a single uninterrupted fluidity of time through continuous space. This intersection of different times into one single perpetual movement given by the zoom is finally beautifully encapsulated in the image of the ocean: photography as still and cinema as moving finally juxtaposed, fused into one another as an irreversible interruption of one single gesture. We can easily comprehend now the conceptual graciousness of the slow movement of the camera zoom as possessing, in durational time, a series of amalgamated stillnesses that, when so effortlessly put together, consequently attribute to time its unique character, its livingness: they establish the continuity which ensures its passing. The emergence of the photographic image strings physical time to our temporal reverie.

This temporal reverie could be argued to have another dimension: that of endurance. So many have been the fortunate opportunities that I have had to watch this film, that one singular unexpected humorous moment has stayed in my memory since it took place. I invited a few friends who had never experienced the approaches of «underground», «avant-garde» or «experimental» (call it whatever you want) filmmaking to join me for Wavelength at the Cinematheque in Lisbon. After 10 or 15 minutes of film, one of them asked me if the film was just like this, or if there was any issue with the projection, due to how long this «scene» was taking, and due to how aware of time he was while trying to figure out what’s going on in this apartment. I did not reply. Later, his doubts increased when the film strip started to be tempered with by Snow, and he asked me if there was someone messing with the projector upstairs, if there was something wrong with the film. I could immediately recognize in his look, as long-time friends often do, the blissful honesty in his questioning. Immediately, another of my friends replied: «but look, you can still feel coherence within the space despite the film being out of place; it’s like you are playing with crossing your eyes and doubling the images you can actually see, maybe that’s what the filmmaker wanted, for you to take part in constructing the space». While the third (and final) said: «Dude, it’s like a weird slow-motion trip». I did not reply at any moment during the screening. It was too tempting to listen to their observations, and to try and find out new aspects that I might not have considered until then.

My point with paraphrasing this situation is that, after the screening, while thinking of what happened, I later realized that this manipulation of the film strip not only purposely interrupts our sense of real space and continuous time, as we have already established, but that «it also interrupts the flow of our experiencing a film in such a way that we are reminded that we are watching the flowing of footage through a projector» (Sharits, 1978, p. 33). And Snow does it so in these pronounced ways as if possessed by the refreshing originality of that untutored eye Brakhage so often spoke about, untamed, never tempered, purely curious: «My eye, turning torwards the imaginary, will go to any wavelengths for its sights» (Brakhage, 2017, p. 35). The mechanical and material defects suggested by my fellow friends are, after all, nothing more than a blunt awareness of the used film stocks, the visible splice marks and jumpcuts, as well as the superimposition of the overexposed and negative celluloid as clear physical constituents of what film literally is — a chemical and material surface sensible to light. Consequently, their presence in the film alludes to what Annette Michelson termed as a visual obbligato: they create, «within the movement forward, a succession of fixed or still moments» we must be confronted with and acknowledge, for they are precisely the unique events that articulate an allusion to the stillness and separateness of the frames out of which the persistence of our corresponding vision organizes into cinematic illusion» (Michelson, 2019, p. 17-18). By removing the celluloid out of its continuous flow, by superimposing it with itself, Snow reminds us that we are also part of the whole mechanism, that the system of a projected film works because the apparatus plays by way of a certain cadence within our human visual organism: the medium begs to be seen, it speaks to me.

If we go deeper in our investigation, what happens, even further, is that the still-image of the sea encompasses, approaching us all the way from the opposite wall towards the framing of the whole screen, a similar conic structure to that of the direction that the still-frames are undertaking in their successive animation, respectively, from the mechanism of the projector, in the corresponding opposite side, towards their destined projection onto the canvas. «Snow understood the vectorial implications of the projector light beam and this seems to account, at least in part, for Wavelength’s directional structure. Physically, the conic shape is directed toward the projector lens; yet, we sense the internal projectiveness of the beam directing itself toward the screen, as if magnitude was its target» (Sharits, 1972, p. 33). It is this moving stillness encapsulated in the photograph along with its protrusion towards our gaze, as well as the sudden rupture of the materiality of the film strip, that allow Snow to bring a phenomena, that we sprout it into being.

Kuleschov, Pudovkin, Eisenstein, Hitchcock, Godard, have frequently taught us that the concept of montage is a confrontation between two images that always originate a new one, and so, in cinematic terms, one plus one is always three, never two. But the studies of Kuleschov underlie a crucial argument relevant to our investigation here: when he proceeds to put the image of the same man in relation to the plate of soup, to a girl in a coffin or to the woman in a divan, he not only argues that our perception of an experience and our search for its meaning is built or unveiled from the relationship inbetween the different shots within it is integrated, the sequence it inhabits, the scenes that precede or those that follow, but, beyond that, he also demonstrates that our perception, the spontaneous understanding of our surroundings, unfolds according to the general principle of Gestalt psychology: it is shaped by a grouping of several elements, by a configuration of different stimuli (sensa) presented to all of my senses all at once, without any immediate need to cirurgically analyse each element individually.

But why is this relevant to us? Because, like many artists in the 60s and 70s, Snow is deeply familiar with the principles of the new psychology, and takes advantage of its basic elements to not only address its functionality, but to build a re-ordering of the habitual gestaltian structure in the same way Jackson Mac Low creates a re-ordering of lexical words through the lyricism of his Gathas, inducing a xamanic-like experience in the reader, or in the same way John Cage removed familiar objects out of their mundane role in our daily routines to elevate them to unexpected musical instruments. All of the letters and words used by Mac Low, all of the objects used by Cage, and all of the film strips used by Snow, are immediately recognizable, they are present to us as familiar objects, as immediate references to habitual signs, but their grouping is not, consequently enticing on us a completely fresh new experience with the medium. So, what are these artists (Snow, Mac Low, Cage) doing? They are looking at the skies, the universe, and realizing that constellations are only born within the eye of the beholder, they present only one possibility to connect a selection of stars amongst eternity. And so, Snow chooses to address other stars whose qualities have always been there, but never actually truly seen. By bringing to the surface the different qualities that compose the structure of the cinematic experience, most of which we are usually unaware of in most narrative or commercial films, Snow unveils the phenomenological nature of film as, following Merleau-Ponty, a temporal gestalt, enticing on us the realization that the possibilities of montage go way beyond the realm of linguistic signification and its beautiful ramifications, be them poetic, metaphorical, symbolical, and so on, for its structural power can be transferred in and out, between and beyond, via a subversion of that semantics, to the sensible and physical world of the materiality of the celulloid (Sharits would explore this in a tremendous way), to the cosmology of perceptual awareness (Brakhage goes even deeper in this aspect, by exploring entoptic phenomena and closed-eye vision, in a clear relationship between the celluloid and the retina) or to the tangible realm of bodily interferences and rhytmic cadences (with Back and Forth’s repetitive movement, and culminating in La Region Centrale, for example, where I’ve seen people falling during screenings because they are enticed by the movement of the camera which shatters any sense of gravitational force). And so, towards Snow, whilst leaning on Paul Klee, we must argue that cinema «does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible» (Klee, 1920, p.1), or, as Merleau-Ponty so elegantly states, «I do not think the world in the act of perception: it organizes itself in front of me» (Merleau-Ponty, 2019, p. 104).

Kuleschov, Pudovkin, Eisenstein, Hitchcock, Godard, have frequently taught us that the concept of montage is a confrontation between two images that always originate a new one, and so, in cinematic terms, one plus one is always three, never two. But the studies of Kuleschov underlie a crucial argument relevant to our investigation here: when he proceeds to put the image of the same man in relation to the plate of soup, to a girl in a coffin or to the woman in a divan, he not only argues that our perception of an experience and our search for its meaning is built or unveiled from the relationship inbetween the different shots within it is integrated, the sequence it inhabits, the scenes that precede or those that follow, but, beyond that, he also demonstrates that our perception, the spontaneous understanding of our surroundings, unfolds according to the general principle of Gestalt psychology: it is shaped by a grouping of several elements, by a configuration of different stimuli (sensa) presented to all of my senses all at once, without any immediate need to cirurgically analyse each element individually.

But why is this relevant to us? Because, like many artists in the 60s and 70s, Snow is deeply familiar with the principles of the new psychology, and takes advantage of its basic elements to not only address its functionality, but to build a re-ordering of the habitual gestaltian structure in the same way Jackson Mac Low creates a re-ordering of lexical words through the lyricism of his Gathas, inducing a xamanic-like experience in the reader, or in the same way John Cage removed familiar objects out of their mundane role in our daily routines to elevate them to unexpected musical instruments. All of the letters and words used by Mac Low, all of the objects used by Cage, and all of the film strips used by Snow, are immediately recognizable, they are present to us as familiar objects, as immediate references to habitual signs, but their grouping is not, consequently enticing on us a completely fresh new experience with the medium. So, what are these artists (Snow, Mac Low, Cage) doing? They are looking at the skies, the universe, and realizing that constellations are only born within the eye of the beholder, they present only one possibility to connect a selection of stars amongst eternity. And so, Snow chooses to address other stars whose qualities have always been there, but never actually truly seen. By bringing to the surface the different qualities that compose the structure of the cinematic experience, most of which we are usually unaware of in most narrative or commercial films, Snow unveils the phenomenological nature of film as, following Merleau-Ponty, a temporal gestalt, enticing on us the realization that the possibilities of montage go way beyond the realm of linguistic signification and its beautiful ramifications, be them poetic, metaphorical, symbolical, and so on, for its structural power can be transferred in and out, between and beyond, via a subversion of that semantics, to the sensible and physical world of the materiality of the celulloid (Sharits would explore this in a tremendous way), to the cosmology of perceptual awareness (Brakhage goes even deeper in this aspect, by exploring entoptic phenomena and closed-eye vision, in a clear relationship between the celluloid and the retina) or to the tangible realm of bodily interferences and rhytmic cadences (with Back and Forth’s repetitive movement, and culminating in La Region Centrale, for example, where I’ve seen people falling during screenings because they are enticed by the movement of the camera which shatters any sense of gravitational force). And so, towards Snow, whilst leaning on Paul Klee, we must argue that cinema «does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible» (Klee, 1920, p.1), or, as Merleau-Ponty so elegantly states, «I do not think the world in the act of perception: it organizes itself in front of me» (Merleau-Ponty, 2019, p. 104).

This observation allows us to go even deeper and, under a second, third or even fourth analysis, finally assert that not only the filmstrip but the whole of the systematic mechanism fulfils the projector’s destined role, yielding its posture as the parallel to our perceptual act, for both the directional movement and the stillness of the photograph enduring in and into time bring forth the juxtaposition of the light beam against the canvas, the windows of the loft against the window of the screen and, ultimately, the frames of my eyes superimposed against the frames of the canvas, such is the open void. Two gestures reaching out from both their horizons now pressed together into an entangled mutuality. It is not by mere chance that Snow himself states how windows and frames are a tremendously influential device: «They seem like metaphors for the eyes in the head; when you're in the house you're looking out the eyes and we are the brains. That was one thing I was thinking about in making Wavelength» (Snow, 1994, p. 196). And so, elegantly, our perceptual apparatus slowly fuses with the cinematic mechanism until the eerie sound finally snaps both bodies — organic and medium — finally together: «When the electronic sound in Wavelength reaches an ear-cracking shriek, the one-shot movie, a forty-five-minute zoom aimed at four splendid window rectangles, burns hot white, like the filaments in a light bulb» (Polito, 2009, p. 1130). The flame ignited by the friction inbetween all of these elements transposes the energetic current running through its filaments directly into the blood flowing in my veins. The continuous stimulus begins to burn both inside my brain and chest, these aural frequencies start to synchronize with the beating of my nervous system, and so the emptiness to this open field is brought into the fold. Through my awareness of its structure, my perception becomes effortless, like an open window allowing a house to breathe, and so I finally realize that I not only live inside and through this house, but that the house also lives through me.

During another interview with Simon Hartog, Snow is questioned about the beginning and ending of the film, taking this temporal discussion even further, «Aren’t the beginning and the end arbitrary?», to which he replies «From the beginning the end is a factor. In the context of the film the end is not arbitrary, it is fated» (Snow, 1994, p. 51). William C. Wees (1992) explores this relationship between beginning-ending in Light Moving in Time by arguing that, through the zoom, the mechanical eye of the lens creates a perceptual experience which cannot be replicated by the human eye: the wall seems, at times, to come forward to meet the viewer, contrary to the natural setting of the spectator (or the screen) walking (moving) towards the wall. In short, a play of vection is triggered, taking Wees to characterize the zoom as embedded with a sort of duplicity: an expansion but also a flattening process of the image.

But this dual process is not only perceptual, again, but conceptual. As Deleuze mentions, «from this room he extracts a potential space, whose power and quality he progressively exhausts» (Deleuze, 2009, p. 122). By establishing such a long zoom, Snow completely wears out the space until reaching its breaking point that, at least in a great part of the first section of the film, has no way of being alleviated, generating a kind of entropic tension or pressure that is only aleviated by the slow adherence of the photography moving towards us, the audience. There is a sensation of density between the fact that the camera is fixed but we keep gradually moving in space, towards the wall, only to finally realize that the space moves, as well, in our direction. What is invisible or imperceptible as potential matter in the beginning of the film, now progressively gains form as a small dot or smudge on the screen, finally revealing itself to be the actual central destiny of the entire piece: «The camera, in the movement of its zoom, installs within the viewer a threshold of tension, of expectation; within one the feeling forms that this area will be coincident with a given section of the wall, with a pane of the window, or perhaps — in fact, most probably — with one of the rectangular surfaces punctuating the wall’s central panel and which seems at this distance to bear images, as yet undecipherable» (Michelson, 1971, p. 4).

Not only that, but this action towards the center entices an equal attention to the corners of the image, since they are always vanishing and changing into something new. Snow imposes in the audience a state of concentrated sight. Our perception of space becomes increasingly limited as we move throughout the zoom, but the more it is excluded by the tightening frame the more it actually reveals.

During another interview with Simon Hartog, Snow is questioned about the beginning and ending of the film, taking this temporal discussion even further, «Aren’t the beginning and the end arbitrary?», to which he replies «From the beginning the end is a factor. In the context of the film the end is not arbitrary, it is fated» (Snow, 1994, p. 51). William C. Wees (1992) explores this relationship between beginning-ending in Light Moving in Time by arguing that, through the zoom, the mechanical eye of the lens creates a perceptual experience which cannot be replicated by the human eye: the wall seems, at times, to come forward to meet the viewer, contrary to the natural setting of the spectator (or the screen) walking (moving) towards the wall. In short, a play of vection is triggered, taking Wees to characterize the zoom as embedded with a sort of duplicity: an expansion but also a flattening process of the image.

But this dual process is not only perceptual, again, but conceptual. As Deleuze mentions, «from this room he extracts a potential space, whose power and quality he progressively exhausts» (Deleuze, 2009, p. 122). By establishing such a long zoom, Snow completely wears out the space until reaching its breaking point that, at least in a great part of the first section of the film, has no way of being alleviated, generating a kind of entropic tension or pressure that is only aleviated by the slow adherence of the photography moving towards us, the audience. There is a sensation of density between the fact that the camera is fixed but we keep gradually moving in space, towards the wall, only to finally realize that the space moves, as well, in our direction. What is invisible or imperceptible as potential matter in the beginning of the film, now progressively gains form as a small dot or smudge on the screen, finally revealing itself to be the actual central destiny of the entire piece: «The camera, in the movement of its zoom, installs within the viewer a threshold of tension, of expectation; within one the feeling forms that this area will be coincident with a given section of the wall, with a pane of the window, or perhaps — in fact, most probably — with one of the rectangular surfaces punctuating the wall’s central panel and which seems at this distance to bear images, as yet undecipherable» (Michelson, 1971, p. 4).

Not only that, but this action towards the center entices an equal attention to the corners of the image, since they are always vanishing and changing into something new. Snow imposes in the audience a state of concentrated sight. Our perception of space becomes increasingly limited as we move throughout the zoom, but the more it is excluded by the tightening frame the more it actually reveals.

As Wavelength permits us to perceive the interpenetration of beginning and end, so it also makes visible the interpenetration of time and space: the viewing time of the film expressed as a center-to-peripheries expansion in space. With the passage of time, every minuscule change in the lens’ focal length marks another expansion of the center toward the borders of the frame. As the film’s time gets longer, its space gets flatter and its central image larger. The paradox of a center expanding to its own peripheries and a beginning containing its own ending is potentially present in every zoom shot, but the zoom in Wavelength makes that paradox visible and invests in it with metaphysical significance. (Wees, 1992, p. 157)

Beginning and ending are inherently intertwined between space and time. We can clearly affirm that, in space, the expansion of the studio contains the black and white photograph as an object within the room, in the same way as it holds the ideal scenario for any human action to take place; but, in time, the photograph of the sea waves undermines space, it besieges space, taking a hold of the apparent vessel which once contained it. And so we finally understand the title of the film, Wavelength, as a concrete correspondence between the two expressions carrying all these entangled qualities: in the expression of the moving-image, we experience both an extension and compression of a visual wave, the photograph of the sea, along the length of our (the camera’s) gaze piercing through the screen across the entire space of the studio, from a wide shot (macro) to an extreme close-up (micro); in the aural expression, we experience a sound wave whose length moves gradually along a low-end (macro) to a high-end (micro) frequency, piercing the systematic expectancy of a figurative reference to an apparent awareness of our sense of hearing. And so we end up wrapped around this resistant image of the ocean, swallowed into the depths of its perceptual abyss, entangled to it as if by strings attached from its waves into the whole of our sensible organic nervous system, just like tides harmoniously stringed to the moon.

References:

Bazin, André (2005) What is Cinema: Volume I. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24227-2

Stan, Brakhage (2017) Metaphors on Vision. New York: Anthology Film Archives. ISBN: 0997910208

Deleuze, Gilles (2009) A Imagem-Movimento: Cinema I. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim. 2nd Edition. Portuguese Translation by Sousa Dias. ISBN: 978-97237-0958-2.

Johnnson, Ken (1994) ‘Being and Seeing’, Art in America, Vol 82, No. 7, July, pp. 70-77, p. 109. Springfield, Massachusettes. ISSN 0004-3214.

Jordan, Randolph (2010) ‘Transcendendo a Fragmentação da Experiência: o acousmêtre no ar nos filmes de Michael Snow’, Arte & Ensaios, Vol 17, N 21, December, pp. 159-177. Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 1516-1692.

Klee, Paul (1920), Creative Confession. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84976-267-0

Lippit, Akira Mizuta (2012) Ex-Cinema: From a Theory of Experimental Film and Video. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 978- 0- 520- 27412- 9

Medeiros, Margarida (2010) Fotografia e Verdade: uma história de fantasmas. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim. ISBN 978-972-37-1561-3.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2019) ‘The Film and the New Psychology’, in Kul-Want, Christopher (ed.) Philosophers on Film: from Bergson to Badiou. New York: Colombia University Press, pp. 97-112. ISBN 9780231176033.

Michelson, Annette (2019) Michael Snow. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 9780262537728

Polito, Robert (ed.) (2009) The Complete Writings of Manny Farber. New York: The Library of America. ISBN: 978-1-59853-470-2.

Sharits, Paul (1978) ‘Words per Page’, Film Culture – Paul Sharits, no. 656-66, 1978, pp. 29-43.

Sitney, P. Adams (2002) Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition. ISBN: 0-19-514885-1.

Snow, Michael (1994) The Collected Writtings of Michael Snow. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-243-5.

Wees, William C. (1992) Light Moving in Time: Studies in the Visual Aesthetics of Avant-Garde Film. Berkeley: University of California Press.

White, Duncan (ed) (2011) Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN: 978-1-85437-974-0.

Bazin, André (2005) What is Cinema: Volume I. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24227-2

Stan, Brakhage (2017) Metaphors on Vision. New York: Anthology Film Archives. ISBN: 0997910208

Deleuze, Gilles (2009) A Imagem-Movimento: Cinema I. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim. 2nd Edition. Portuguese Translation by Sousa Dias. ISBN: 978-97237-0958-2.

Johnnson, Ken (1994) ‘Being and Seeing’, Art in America, Vol 82, No. 7, July, pp. 70-77, p. 109. Springfield, Massachusettes. ISSN 0004-3214.

Jordan, Randolph (2010) ‘Transcendendo a Fragmentação da Experiência: o acousmêtre no ar nos filmes de Michael Snow’, Arte & Ensaios, Vol 17, N 21, December, pp. 159-177. Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 1516-1692.

Klee, Paul (1920), Creative Confession. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84976-267-0

Lippit, Akira Mizuta (2012) Ex-Cinema: From a Theory of Experimental Film and Video. Los Angeles: University of California Press. 978- 0- 520- 27412- 9

Medeiros, Margarida (2010) Fotografia e Verdade: uma história de fantasmas. Lisbon: Assírio & Alvim. ISBN 978-972-37-1561-3.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (2019) ‘The Film and the New Psychology’, in Kul-Want, Christopher (ed.) Philosophers on Film: from Bergson to Badiou. New York: Colombia University Press, pp. 97-112. ISBN 9780231176033.

Michelson, Annette (2019) Michael Snow. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 9780262537728

Polito, Robert (ed.) (2009) The Complete Writings of Manny Farber. New York: The Library of America. ISBN: 978-1-59853-470-2.

Sharits, Paul (1978) ‘Words per Page’, Film Culture – Paul Sharits, no. 656-66, 1978, pp. 29-43.

Sitney, P. Adams (2002) Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde. Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition. ISBN: 0-19-514885-1.

Snow, Michael (1994) The Collected Writtings of Michael Snow. Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 0-88920-243-5.

Wees, William C. (1992) Light Moving in Time: Studies in the Visual Aesthetics of Avant-Garde Film. Berkeley: University of California Press.

White, Duncan (ed) (2011) Expanded Cinema: Art, Performance, Film. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN: 978-1-85437-974-0.